9/11- A Swift Response

(Originally published on December 14, 2022.)

A guilt-ridden rage prevailed at CIA Headquarters the morning of 9/11. We were the nation’s first line of defense against international terrorism. We knew that Osama bin Laden was determined to attack the US homeland. Yet, we had failed to prevent it.

This rage animated an unbelievably swift response. We would have to deal first with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan that protected Bin Laden. Then, we would find him.

Cofer

Two days after the attack, on the morning of 13 September, President Bush was in a vengeful mood when he met with his war cabinet.* Secretary of Defense Don Rumsfeld dropped the bombshell that General Tommy Franks would need at least two months to launch a major military assault on Bin Laden’s refuge in Afghanistan. Secretary of State Colin Powell could sense that the President wanted Bin Laden dead now. CIA Director George Tenet introduced his legendary counterterrorism director, Cofer Black.

Cofer said, ‘Mr. President, we can do this. You’ve got to understand that people are going to die, Americans are going to die, my colleagues and friends.’

‘That’s war,’ the President responded guardedly.

Cofer explained how a team of CIA officers providing political top cover, Special Forces providing precision bomb targeting, and massive US air power could enable our Afghan partners in the so-called Northern Alliance to rout the Taliban. ‘You give us the mission and when we are through with them, they will have flies walking across their eyeballs.’

When the President asked about the Northern Alliance leadership, Cofer gave an honest assessment. Northern Alliance leaders were from different ethnic groups, they bickered, and they were not necessarily nice guys. They were motivated to fight the Taliban, however, and were susceptible to CIA money.

‘How long will it take?’ the President asked.

Cofer responded confidently, ‘Once we are on the ground, it will be a matter of weeks, not months.’ Not even Director Tenet believed this.

A novice at foreign policy but an experienced manager of talented teams, the President wanted to hear more about Cofer’s plan. In large part, this was because the President wanted to prod the Pentagon into thinking more aggressively. A follow-on meeting was scheduled for Saturday, 15 September, at Camp David.

Gary

At the Camp David meeting, Director Tenet gave a comprehensive briefing entitled “Going to War.” It was stunning in its sweep. At its heart was a request for exceptional authorities to allow the CIA to do whatever necessary to destroy Bin Laden’s Al Qaeda, first in Afghanistan and then in the rest of the world.

The President was impressed. Secretary Rumsfeld kibitzed but admitted that the military could do very little immediately. So, after expedited legal review, the President signed the necessary paperwork to unleash the CIA the following Monday.

With this in hand, Cofer called one of the true heroes at CIA, Gary Schroen. Overweight and 59 years old, Gary was in the process of retiring, but he knew all the players in Afghanistan and spoke Pushto and Dari, the two principal languages of the country. Cofer asked him to postpone his retirement and lead the first CIA team into Afghanistan. Gary agreed on the spot.

Gary’s team would test dangerous waters. There would be no rescue if things went awry. Their job was to go in, verify that the leadership of the Northern Alliance would work with the US, and prepare the ground to welcome US Special Forces.

‘You have another mission,’ Cofer added. ‘Get Bin Laden. I want his head in a box to show the President.’

After getting outfitted at the REI in Tysons Corner, Gary and a small team of CIA officers departed Washington on 20 September and arrived in the Panjshir Valley of northeastern Afghanistan on 26 September, a mere 15 days after the 9/11 attacks.

Bob

One of CIA’s most powerful tools and used sparingly is the Chief of Station Field Appraisal. On 23 September, COS/Islamabad Bob Grenier sent such an appraisal to Washington. In it, he stressed that for success the war had to be cast as the Afghans versus the Al Qaeda foreigners. The US should underscore that we had no desire for permanent bases in Afghanistan and that Afghans themselves should decide how best to govern Afghanistan. The US was there only to help Afghans evict Al Qaeda just as we had helped Afghans evict the Soviet in the 1980’s.

At a meeting of his war cabinet on 24 September, the President directed that Bob’s Field Appraisal, ‘Should be the template for our strategy. We should use the Afghans in the struggle.’

Director Tenet assured, ‘The Chief of Station and Tommy Franks will discuss this.’

General Franks

Tommy Franks is a great warrior. After dropping out of the University of Texas at Austin, he enlisted in the Army in 1965 at age 20. In 38 years of service, he rose from Buck Private to Four Star General and, on the way, won 3 Purple Hearts. An Old Army artilleryman, General Franks was superbly prepared to lead the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He was not well suited, however, to coordinate our 2001 intervention in Afghanistan.

In the overthrow of the Taliban regime, the fighting was done by the Afghans, as the President directed. To support the Afghans, the US committed a small number of CIA officers and Special Forces personnel plus overwhelming airpower.

This was a job for a One Star, not a Four Star. It was the most important command of a lifetime, however, so understandably General Franks had a hard time letting go.

Tensions Mount in the War Cabinet

In the Panjshir Valley, Gary had answered the two key questions by 28 September. Yes, the Northern Alliance would work with the US. Yes, it was as safe as it would ever be for the arrival of US Special Forces.

In Washington, the President wanted to initiate military operations as soon as possible and suggested 1 October.

General Franks, however, did not begin the bombing campaign until 7 October. Even then it focused on stationary targets in southern Afghanistan, far from the Taliban front lines in the north.

As of 15 October, the Special Forces were frustrated that Franks’ chain of command would still not allow them on the ground in Afghanistan where they could direct precision airstrikes against the Taliban front lines. Secretary Rumsfeld was equally frustrated that CIA had shown the agility to place a team on the ground in Afghanistan, but Franks could not.

Rumsfeld had been there when American Airlines Flight 77 slammed into the building on 9/11. He had gone to the scene personally to offer his help with the wounded and dead. At the war cabinet meeting of 16 October, Secretary Rumsfeld lost control of his emotions, ‘This is just the CIA strategy.’

Representing CIA that day, Deputy Director John McLaughlin tried to assuage Rumsfeld, ‘We are supporting General Franks. General Franks is in charge.’

‘No, you guys are in charge,’ Secretary Rumsfeld corrected. ‘You guys have the contacts. We’re just following you in. We’re going where you tell us to go.’

Deputy Secretary of State Rich Armitage, no fan of Rumsfeld, said, ‘This is FUBAR. Who is in charge out there? Who is taking responsibility on the ground?’

Angry at this display of disunity, the President ordered National Security Advisor Condi Rice, ‘Get this mess straightened out.’

Hank

On 9/11, Hank Crumpton had just moved with his family to an enjoyable overseas assignment. In the immediate wake of the attack, Cofer asked Hank to cancel the assignment, return immediately to headquarters, and take over CIA Special Operations in Afghanistan. Hank agreed, leaving his wife to move the family back to Washington.

Hank hung a sign outside his headquarters office taken from a 1914 recruiting poster for an expedition to Antarctica. It read, “Officers wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages. Bitter cold. Long months of complete darkness. Constant danger. Safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in case of success.”

It fell to Hank to make General Franks as comfortable as possible with the strategy and, at all costs, get things moving on the ground in Afghanistan.

Thanks to the President’s continued prodding, the first Special Forces team finally arrived in country on 19 October. Hank made sure that Gary and his team were on hand to warmly greet them. Thereafter, a steady stream of CIA officers and Special Forces teams arrived and together fanned out around the country.

There was still an issue with the airstrikes. Stationary targets in southern Afghanistan were for some reason still receiving priority; the Taliban front lines were only secondary targets. With Hank’s encouragement, Gary used his position as the senior US official in country to send Washington a COS Field Appraisal on 26 October. Director Tenet showed it to the war cabinet the next day.

In his Field Appraisal, Gary argued for sustained bombing of the Taliban front lines. He was on the ground and had more experience in Afghanistan than any other American. He knew that after just 3-4 days of sustained bombing, the Taliban front lines would collapse and open the way for the Northern Alliance to capture Mazar-e-Sharif first and then the capital, Kabul.

General Franks scoffed at the idea. On 2 November, he told the President, ‘I don’t place any confidence in the Northern Alliance.’ He agreed to Gary’s request, but at the same time he would work on a plan to Americanize the war by expanding US troop presence to 50,000.

The President hoped that Gary was right but needed a fallback, ‘When can you give me some options,’ he asked General Franks.

‘In one week,” Franks replied.

The Taliban Collapse

The sustained bombing of the front lines had exactly the effect that Gary predicted – the Taliban collapsed.

On 9 November, exactly one week after General Franks scoffed at the idea, the Northern Alliance captured Mazar-e-Sharif.

On 13 November, exactly two months after Cofer Black told the President, ‘We can do this,’ the Northern Alliance captured Kabul.

Most Taliban troops surrendered in mass. The Taliban leadership and all surviving Al Qaeda fled.

This stunning success was achieved without a single death among US personnel.**

Bin Laden and Zawahiri Escape

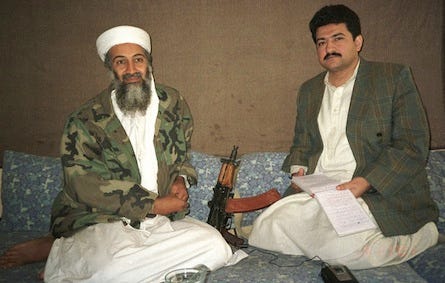

On 8 November, the day before the fall of Mazar-e-Sharif, Osama bin Laden and his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri were interviewed in Kabul by the noted Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir. Bin Laden was very confident. You can read the interview on-line (Osama Claims He Has Nukes, by Hamid Mir, 10 November 2001).

Things changed dramatically over the next 5 days. On the morning of the 13th, American B-52’s struck the Kabul front. From 2,000 meters away the pounding was terrifying, one could only imagine what it was like being closer. Those not killed immediately fled for their lives. Bin Laden’s operations chief, Mohamed Atef was killed. The Taliban’s Mullah Omar was heard on the radio beseeching his troops to regroup in the traditional Pashtun strongholds in the south and the east along the border with Pakistan.

Circa 13 November, Bin Laden and Zawahiri fled east to Al Qaeda’s mountain redoubt in Tora Bora. Tragically, the US Government lost focus at this critical moment. As a result, we let them slip through our fingers into Pakistan sometime during 14-16 December.

The story of that escape and the terrible, long term political consequences will be the subject my third and final posting related to 9/11.

(*) This posting is distilled from Bob Woodward’s 2002 book Bush at War.

(**) The first death among American personnel in Afghanistan was CIA officer Mike Spann who was killed on 25 November near Mazar-e-Sharif in a riot of Taliban prisoners.