(Originally published on August 30, 2023)

This is the last of three essays I will write regarding the direct impact of 9/11 on American history. The first essay - The Attack - was published last year on the 21st anniversary of 9/11. The second essay - A Swift Response - was published on 14 December 2022, the 21st anniversary of when the US Government lost focus and allowed Osama bin Laden to escape into Pakistan. This third essay deals with the terrible strategic consequences of our failure to finish off Bin Laden in December 2001 and is published today, the second anniversary of our final withdrawal from Afghanistan.

There is no doubt that Osama bin Laden was cornered in his stronghold of Tora Bora along the Afghan border with Pakistan on 14 December 2001. Eyewitness accounts place him there. The senior CIA officer at the scene, Gary Berntsen, and the commander of US Special Forces at the scene, Major Thomas Greer, knew Bin Laden was there because they were listening to his radio communications. The deputy commander of CENTCOM, Lieutenant General Michael Delong said, “He was definitely there when we hit the Tora Bora caves.” At the time, even CENTCOM Commanding General Tommy Franks was convinced, although he backpedaled in an October 2004 New York Times op-ed. (Shortly thereafter, an angry Major Greer retired from the Army and, under the pen name Dalton Fury, wrote the book Kill Bin Laden. Greer died of pancreatic cancer in 2016 at age 52.)

Through their separate chains of command, Berntsen and Greer recommended that a battalion of 800 American troops be sent in to seal off the border and prevent Bin Laden from escaping into Pakistan. Jim Mattis, then a One-Star and the senior US military commander in Afghanistan at the time, concurred with this recommendation and had the troops available. Back in Tampa and preoccupied with Iraq war planning, the Four-Star General Franks rejected the recommendation.

Berntsen’s CIA boss in Washington, Hank Crumpton, pleaded with President Bush to overrule Franks and deploy the 800 American troops. Stressing that it was beyond Pakistani military capability to seal the border, Crumpton recommended that the US military should at least try.

But Franks judged that Bin Laden could not survive. He was trapped between Afghan troops to his front, Pakistani troops along the border to his rear, and brutal American airstrikes directed by the US Special Forces raining down from above. There was no need to put the additional 800 American troops in harm’s way. After due consideration, the President deferred to his commanding general’s judgement.

The battle of Tora Bora ended on 17 December. A video tape surfaced on 26 December showing a haggard Bin Laden seemingly wounded on his left side but still alive. It was not clear when the video was taken – before or after 17 December – or where – still in Afghanistan or in the safety of Pakistan. The President of Pakistan expressed confidence that Bin Laden had been killed in the bombing of Tora Bora after the video had been taken. But Bin Laden’s body could not be found.

For close to three years, the US Government did not know Bin Laden’s fate for certain. A number of audio tapes surfaced purporting to be from him and a few video tapes, but the uncertainty about his fate persisted. This was of monumental political importance because immediately after 9/11 President Bush had publicly vowed to track down Bin Laden and get him “dead or alive.”

Stuck in Afghanistan

The consequence of this uncertainty about Bin Laden was that President Bush was stuck in Afghanistan. Afghanistan was the essential base of operations in the hunt for Bin Laden. Defense Secretary Don Rumsfeld wanted to shift troops and focus on Saddam Hussen and Iraq but he couldn’t abandon the hunt for Bin Laden entirely. As a result, American troop levels in Afghanistan rose steadily from 2,500 in December 2001 to 9,700 in December 2002. In May 2003, Rumsfeld declared the end of major combat operations in Afghanistan but American troop levels there still kept rising to 13,100 in December 2003, with their focus on building a new Afghan Army from scratch.

On 29 October 2004, just four days before the Bush-Kerry presidential elections, a 15-minute video was released of Bin Laden that was unequivocally current. Posing as an Islamic saint in a pure white robe and golden shawl, a healthy Bin Laden taunted Bush on how easy it was for Al Qaeda to bait and mislead America. Our troop levels duly increased to 20,300 in December 2004.

The new Bin Laden video marked a turning point in the Afghan insurgency. Beginning in 2005, the Taliban, taking a lesson from insurgents in Iraq, made greater use of suicide bombers and Improvised Explosive Devices (IED’s), particularly targeting American troops. By mid-2006, there was a full-fledged insurgency underway in the rural areas of southern and eastern Afghanistan. American military deaths in country almost doubled from 52 per year in 2002-2004 to 99 per year in 2005-2006.

The President and his new Defense Secretary Robert Gates reacted to the deteriorating situation by Americanizing the war. This was a major shift in policy. In late 2001, the President had decreed that our template for success was to cast the war as the Afghans versus the Al Qaeda foreigners; the US had no desire for permanent bases in Afghanistan (see essay #2 – A Swift Response.) By late 2006, US troops had been at Bagram Air Force Base outside of Kabul for 5 years and the war had morphed into a contest between the Afghan Taliban and American foreigners.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai loudly criticized this change in American policy. In 2007, Karzai warned that Afghan patience was wearing thin over the increasing number of civilians killed by American forces hunting Taliban insurgents. Many in the US thought Karzai was ungrateful, some thought he was “confused,” some dismissed him as incompetent or corrupt.

US military deaths in country during 2007-2008 increased again to 137 per year. US troop levels rose to 30,000 in January 2008 and close to 50,000 by the end of the Bush Administration.

Enter President Obama

In March 2009, newly elected President Obama clearly defined his policy goals in Afghanistan. His top priority was to get Bin Laden and to “disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al Qaeda.” His second priority was to promote “a more capable, accountable, and effective government in Afghanistan” by “executing and resourcing an integrated civilian-military counterinsurgency strategy.” He ordered 21,000 more troops to Afghanistan and quadrupled the number of US diplomats and civilian aid workers. (Footnote *1)

The President succeeded in achieving his first priority. To defeat Al Qaeda, he de-emphasized efforts to capture terrorist leaders and unleashed armed Predator drones to kill them. Many were surprised but the Obama administration in just its first year killed more terrorists using drones than during the entire Bush administration. CIA Director Leon Panetta called the drone program “the only game in town” and it was brutally effective.

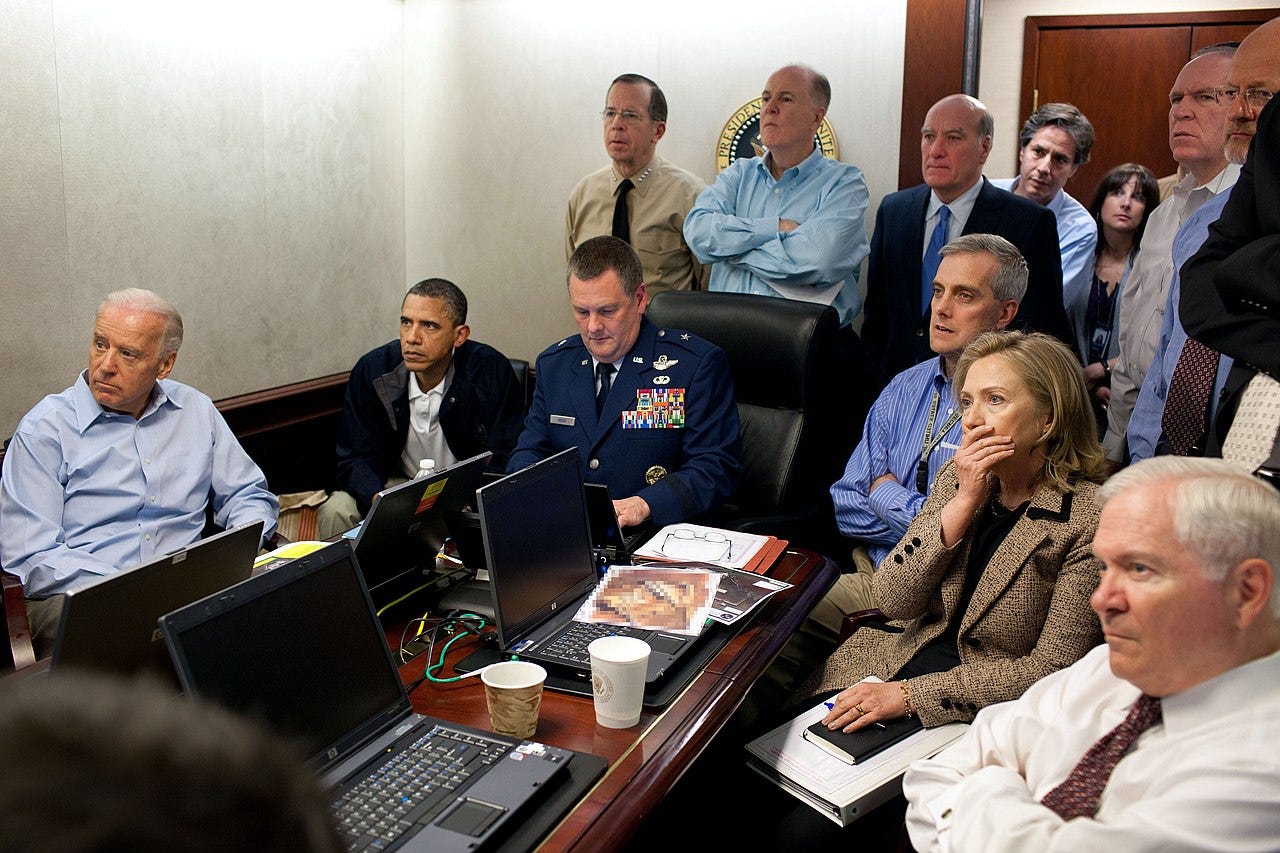

To get Bin Laden, the President made the gutsiest call I have seen in my 40 years of government service. In the fall of 2010, the CIA thought we had located Bin Laden’s hiding place in Abbottabad, Pakistan, just a few miles from that nation’s military academy. We were not absolutely certain but it was the best lead we had developed since Tora Bora. In the imperfect world of intelligence, it was probably the best lead we would ever have.

Assuming it was Bin Laden, the President had to decide whether to (a) bomb the place or (b) send in a Special Forces team. Bombing would be safer but produce the same uncertainty as the bombing had in Tora Bora. The Special Forces would produce certainty but the mission was extremely dangerous. If it ended in disaster as President Carter’s attempted rescue of the Iran Hostages had, then Obama knew he would not be re-elected.

Panetta and Director of National Intelligence Jim Clapper supported sending in the Special Forces. The President’s senior policy advisors were divided. President Obama thanked his policy advisors and, with no further hesitation, sent in the Special Forces. The success was one of the high points of his presidency.

Less successful were Obama’s efforts to encourage good government in Afghanistan. The government of President Hamid Karzai had grown deeply unpopular. His ministers were more committed to the financial well-being of their individual tribal groups than they were to any idea of Afghan national interests. The presidential elections of August 2009 suffered from poor security and low turnout so ballot stuffing and other electoral fraud were widespread. Karzai was declared the winner of a second term but he never re-gained the legitimacy he had enjoyed early in his 2004-2009 term. This lack of governmental legitimacy fed support to the Taliban insurgency.

In May 2009, Obama named the hard-charging, strait-talking General Stanley McCrystal to command the counterinsurgency efforts. He tasked McCrystal with producing an assessment of the troop levels he would need to fulfill his assigned mission. The General’s August 2009 assessment surprised the President. McCrystal said the Taliban insurgency was “resilient and growing.” He called for 80,000 more troops to maximize chances for mission success or 40,000 for a medium chance of success. He offered a third option of abandoning the counterinsurgency mission in favor of a leaner counterterrorism mission. In what the President later said was the hardest decision of his presidency, he gave McCrystal an additional 30,000 troops, which boosted total troop deployments in Afghanistan to over 100,000 in January 2010, its highest level ever.

Results were disappointing. The insurgency intensified. US military deaths skyrocketed to 311 in 2009 and 498 in 2010. Afghan civilian deaths and collateral damage increased as well. American troops were winning tactical battles but strategically losing popular Afghan support, particularly in rural areas far from the prospering capital of Kabul. In July 2010, the President replaced McCrystal with the renowned General Dave Petraeus but the security situation remained dire into 2011.

Obama’s Turning Point

The May 2011 success in getting Bin Laden was the turning point for President Obama regarding counterinsurgency. He had risked his reelection chances based on his confidence in the operational prowess of US Special Forces coupled to the actionable intelligence of CIA. Having won that first bet, Obama was not inclined to put his reelection at risk a second time for the sake of a fractious, corrupt, and illegitimate Afghan government.

On 22 June 2011, the President announced a drawdown of US troops in Afghanistan. 10,000 would depart by the end of the year with another 23,000 departing by the summer of 2012. Thereafter, “our troops will continue coming home at a steady pace” until 2014, at which time “the Afghan people will be responsible for their own security.” Thanks to American support, the Afghan government’s military had grown to 323,000 troops in December 2011 compared to at most 50,000 Taliban insurgents. (FN *2)

Good to the President’s word, US troop levels fell to 64,000 in January 2013 and 33,000 in January 2014. US military deaths dropped precipitously from 411 in 2011 to 55 in 2014. Throughout 2013 and 2014, the Pentagon warned that Afghan troops might be improving but they were not ready to replace US troops and that the Taliban insurgency was regaining lost ground. The White House pushed back noting that Afghan troops would never be able to replace US troops but with a 6 to 1 numerical advantage over the Taliban, something deeper had to explain the gains of the insurgents. The American people needed to know: would the Afghan government fight to defend itself?

In May 2014, the President announced that US troops would be completely withdrawn from Afghanistan by 2016, before the end of his administration. This resulted in considerable US political pushback which notably was bipartisan in nature. Obama eventually bowed to this bipartisan pressure. In October 2015, he announced that 10,000 troops would remain in Afghanistan through 2016 so as not to tie the hands of the next administration, be it Democrat or Republican.

Enter President Trump

Although neither will ever admit it, President Obama and President Trump share a sincere frustration with “endless wars” that divert America’s blood and fortune from pressing issues, both domestic and foreign. For that matter, so does President Biden.

Trump campaigned on putting an end to these “endless wars.” After becoming President, he also named retired General Jim Mattis to be his first Defense Secretary, the same Jim Mattis who in 2001 had wanted to send the 800 US troops to finish off Bin Laden in Tora Bora. The potential for discord in this vitally important relationship was obvious from the start.

After a lengthy review of strategic options by his national security advisors, President Trump made his first Afghan policy pronouncement seven months into his term on 21 August 2017. He admitted that “My original instinct was to pull out – and, historically, I like following my instincts.” He bowed to his security advisors, however, in making three statements about America's core interests.

- We require “an honorable and enduring outcome worthy of the tremendous sacrifices that have been made.”

- “The consequences of a rapid exit are both predictable and unacceptable.”

- “The security threats we face in Afghanistan and the broader region are immense.”

Accordingly, the President said, “America will continue its support for the Afghan government and the Afghan military as they confront the Taliban in the field.” He said that we would “prevent the Taliban from taking over Afghanistan.” He said, “Our troops will fight to win.”

A core pillar of the President’s new strategy was to cease public discussion “about the numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities,” because “America’s enemies must never know our plans or believe they can wait us out.” Indeed, press reports indicated that the President had already authorized Mattis in June to increase Afghan troop deployments to 14,000 from the 10,000 at the end of the Obama administration. (FN *3)

Mattis Resigns

In 2018, the Taliban launched an offensive, including a series of bold terror attacks in Kabul that killed over 100 people. The Afghan Army fought back hard with the support of US airstrikes and US advisors deployed across rural Afghanistan. US military deaths were limited to 16 but the Afghan military and police lost over 10,000 and collateral civilian deaths were the worst on record. US military leaders admitted that the war had reached a stalemate.

On 25 February 2018, the Taliban called for peace talks directly with the US but our long-established policy was not to interfere with internal Afghan discussions. Two days later, on 27 February, the new Afghan President Ashraf Ghani proposed unconditional peace talks with the Taliban, including recognition as a legal political party and release of prisoners. This was a generous offer by Ghani but the Taliban refused to even acknowledge it.

With the stalemate continuing, in September 2018 the President appointed the Afghan-born American Zalmay Khalilzad as his Special Envoy for Afghanistan. Khalilzad was a renowned dealmaker. Trying to move negotiations forward, he met with Taliban leaders in October and again in December but without the presence of Afghan government representatives. In the December talks, the Taliban proposed a peace agreement conditional on a drawdown of US troops. The Afghan government was outraged when they learned about the proposal.

Mattis to this day is mum on what happened but he submitted his resignation letter on 20 December. Later that same day, the Trump Administration broke its own rule and announced that our troop levels in Afghanistan would be cut in half in the following months.

On 29 February 2020, Khalilzad signed a separate deal with the Taliban without Afghan government participation. The deal committed the US to withdraw its remaining troops from Afghanistan by May 2021. The Taliban guaranteed that it would not allow Afghanistan to be used for terrorist activities. With no cease-fire included in the deal, however, the Taliban carried out dozens of attacks on the Afghan government immediately after the signing ceremony. (FN *4)

Mattis was replaced as Defense Secretary by the worthy Mark Esper who served until 9 November 2020, six days after the presidential elections. In a tweet, President Trump fired Esper and named the relatively unknown Christopher Miller as Acting Defense Secretary. On 17 November, Miller took a moment to introduce himself to the Pentagon press corps and then announced that the President had decided to cut troop levels in Afghanistan to 2,500 by 15 January 2021, five days before President Biden assumed office.

Closure by President Biden

The thankless job of closing our long and tragic intervention in Afghanistan was left to newly elected President Biden. Under messy circumstances, he endeavored to mitigate the resulting human and moral trauma.

On 14 August 2021, the President said forthrightly, “I was the fourth President to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan – two Republicans, two Democrats. I would not, and will not, pass this war onto a fifth.” (FN *5)

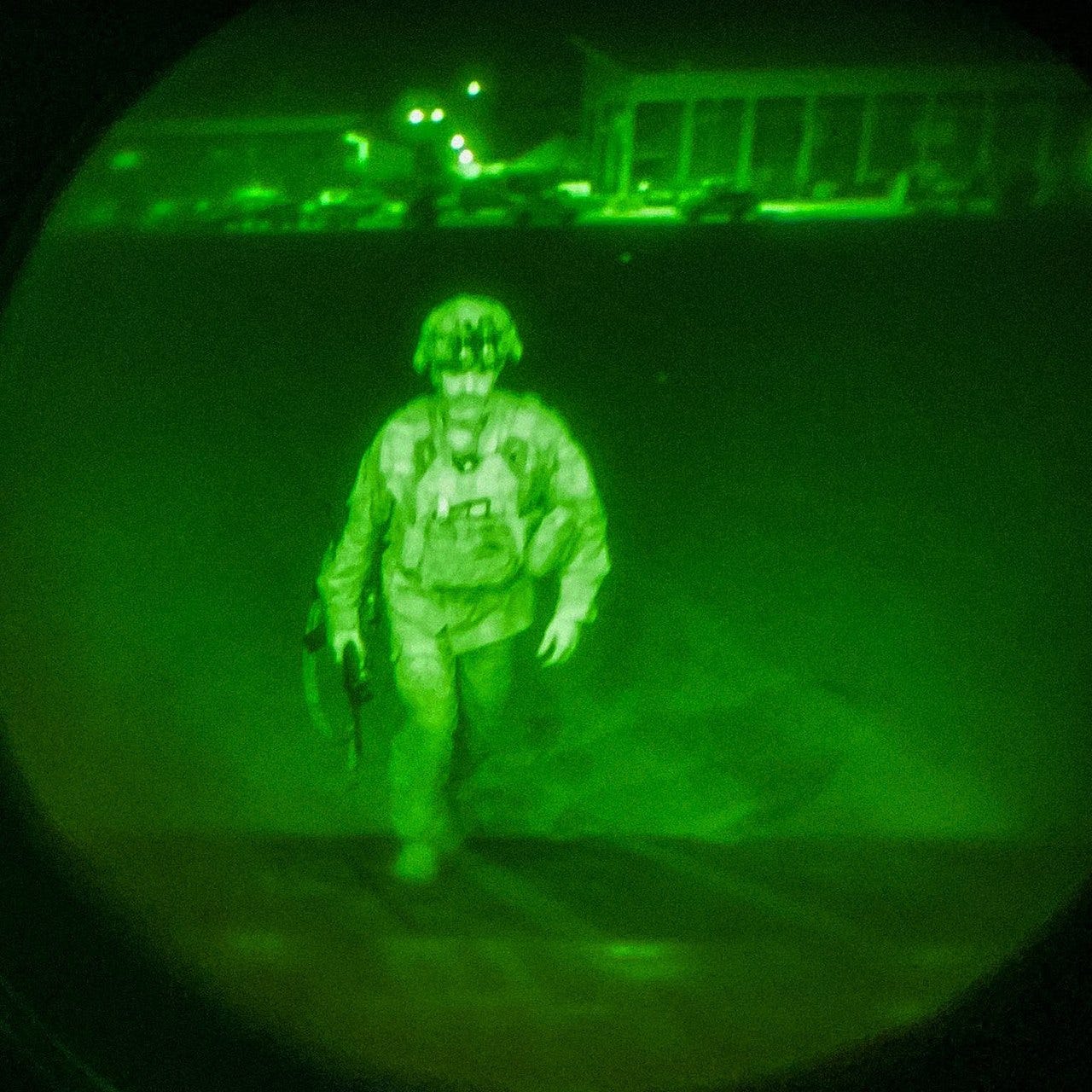

With tens of thousands of Afghans dead, 2,456 US soldiers dead, and $1 Trillion diverted from other important priorities, our last soldier in Afghanistan, Major General Chris Donahue, left on 30 August 2021, two years ago today.

In Hindsight, What Might We Have Done Better

It is painful looking back over these three essays on 9/11. In hindsight, I can only offer some suggestions on what we might have done better.

First and foremost, we could have and should have prevented 9/11. All of us at CIA that terrible day are ultimately accountable for that failure.

Second, we should have tried to finish off Bin Laden at Tora Bora by sending the 800 US troops in harm’s way. We might not have succeeded. But we might have succeeded. The US military high command and President Bush are ultimately accountable for that lack of effort.

Third, after getting Bin Laden, President Obama should have advised the American people of our broad strategic goals and then executed to them as conditions on the ground permitted. By advertising the timelines of our troop drawdowns, the President encouraged the Taliban to “wait us out.”

Fourth, President Trump, having agreed to the August 2017 strategy, should have stuck with it. That strategy was proceeding at limited cost in US lives and treated our Afghan allies honorably. President Trump should not have cut a separate deal with our Taliban foes.

Footnotes

(*1) Remarks by the President on a New Strategy for Afghanistan, 27 March 2009

(*2) Statement by the President on the Way Forward Afghanistan, 22 June 2011

(*3) Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan, 21 August 2017

(*4) Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban and the United States of America, 29 February 2020

(*5) Statement by President Joe Biden on Afghanistan, 14 August 2021

The summary is indeed a tragic reminder of the blood, treasure, and time we spent on this... while peer and near peer adversaries built up their capabilities.