Invading Iraq: An Avoidable Fiasco

(Originally published on October 22, 2024.)

(This is my second of three Substack essays regarding the Second War in Iraq. The first, entitled Invading Iraq: Our Flimsy Justification was published in August 2024. The final essay regarding the adverse long-term impact of the war on America will be published after the upcoming Presidential elections.)

America invaded Iraq on 20 March 2003 but the inter-agency policy debate about the future of Iraq following an invasion began in early 2002. On one side, the State Department argued for an inclusive process in which Iraq’s major ethnic groups – Shia, Sunni, and Kurds – would be brought together to choose genuine leaders. On the other side, the Defense Department wanted to handpick leaders who were amenable to US interests. The Defense Department was particularly enamored with Ahmed Chalabi, an MIT and University of Chicago graduate who had not lived in Iraq since 1958 yet had assured Defense Department leaders that US troops would be welcomed there as liberators.

After a year of inconclusive interagency debate, President Bush got fed up and decided on his own. On 20 January 2003, he signed National Security Presidential Directive 24 giving complete control of post-invasion Iraq to the Defense Department and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

The NSPD 24 decision was informed by our post-World War 2 experience in which the all-powerful military governors General Douglas MacArthur and General Lucius Clay had successfully transformed Japan and Germany into stable democracies allied with the US. It was a slap in the face to Secretary of State Colin Powell, however, who just one week before had committed his support for the President to launch the preemptive war.

The war plan for Iraq prepared by General Tommy Franks began with the statement, “The purpose of this operation is to force the collapse of the Iraqi regime and deny it the use of Weapons of Mass Destruction to threaten its neighbors and US interests in the region”. To achieve this purpose, Franks had an invasion force of 145,000 of which 125,000 were US troops and 20,000 were allied troops mainly from the UK. The opposing Iraqi Army was much inferior in quality but was nearly three times larger at 400,000.

The war plan was unusually controversial in US military circles. In October 2002, Marine Three-Star Greg Newbold resigned from his prestigious position as the Joint Chiefs Operations Director in protest to the plan. Franks predecessor retired Marine Four-Star Anthony Zinni, as well as legendary retired Army Four-Star Barry McAffrey were forthright in their criticism that invasion with such a small force was unnecessarily risky. They believed in the existing US military doctrine of using overwhelming force known as the “Powell Doctrine” after Secretary Powell who a decade previously had served as Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In February 2003, Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki testified in a public meeting of the Senate Armed Services Committee that “several hundred thousand soldiers” would be required to secure and stabilize Iraq following a successful invasion. Shinseki was certainly aware that Pentagon planning at the time was to reduce the troop level in Iraq to only 30,000 by August. Defense Secretary Rumsfeld was furious with Shinseki for getting out of line and thereafter treated him as a Persona non Grata. Taking the hint, Shinseki announced his intention to retire at the end of his term in June.

Mission Accomplished?

Despite several hiccups, the invasion itself seemed to go smoothly. In just two weeks, US forces seized Baghdad airport just west of the city. On 9 April, they took the city itself. To symbolize “the collapse of the Iraqi regime,” a massive statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down for all to see.

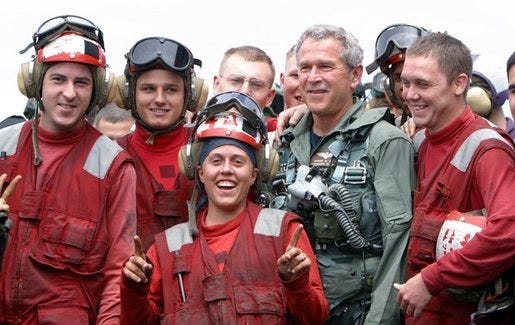

On 1 May, President Bush flew out to the USS Abraham Lincoln off San Diego as a passenger/co-pilot on a four-person naval jet, becoming the first sitting president to make an arrested landing onto an aircraft carrier. After posing in his flight suit with ship crew members, he switched into business attire to make an important speech. Under a banner which read Mission Accomplished, the President proclaimed that, “Major combat operations in Iraq have ended. In the battle for Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.”

In similarly high spirits, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld offered the Army Chief of Staff position to the hero of the hour, 58 year-old General Franks. To Rumsfeld’s surprise, Franks declined. He may have had enough of the domineering Defense Secretary. He wanted to leave on a high note after successfully collapsing the Saddam regime. He also wanted to make some money after having served in the Army since he was 20. So, on 22 May, Tommy Franks announced his own retirement and got out of town.

Al Qa’qaa

One consequence of the risky, small invasion force was that our assault troops did not have the manpower both to take Baghdad and to secure important Iraqi weapons depots. Al Qa’qaa, a huge weapons depot near Salman al Husain 30 miles south of Baghdad, was particularly important. Al-Qa’qaa had been involved in Iraqi WMD work since the late 1980’s and in March 2003 contained 377 tons of powerful HMX and RX high explosives.

These explosives can be used to detonate nuclear weapons. For that reason, the International Atomic Energy Agency used locks and seals to monitor Iraqi stockpiles of them. Tragically for thousands of young American and British soldiers, HMX and RX also turned out to be ideal for use in roadside bombs placed by Iraqi insurgents.

On 5-6 April, elements of the US 3rd Infantry Division rested at Al-Qa’qaa after engaging in heavy combat at the Karbala Gap and the Al-Kaed Bridge over the Euphrates River. On 10 April, elements of the 101st Airborne Division stopped overnight at Al-Qa’qaa. Focused on their push to Baghdad, neither unit knew what was located there nor took action to secure it. (1)

On 18 April, a news crew embedded with the 101st Airborne took film of the IAEA locks and seals still in place protecting the explosives. In late April, the IAEA warned the US Government that the explosives were otherwise unguarded.

Then, on 27 May, the US 75th Exploitation Task Force visited Al-Qa’qaa and discovered that the IAEA seals had been broken and all the explosives stolen. Sometime between 18 April and 27 May, Al-Qa’qaa had been systematically looted by highly organized actors, most likely Iraqi Sunni’s but possibly Iraqi Shia’s. An IAEA memo called the theft “the greatest explosives bonanza in history.”

General Jay Garner

As his first US governor of Iraq, Rumsfeld appointed retired Three Star General Jay Garner in late January 2003. Garner was 65, deeply experienced in the complexities of Iraq, full of common sense, and known for speaking truth to power. He was a worthy heir to MacArthur and Clay … but things unraveled quickly.

First, Garner was not permitted to select his own team. On Friday 21 February, Garner organized his first meeting of Iraq experts from across the US government. He was impressed by two exceptionally well-organized State Department officials named Meghan O’Sullivan and Tom Warrick. Garner invited them to come work for him on detail the following Monday and they agreed to do so. A few days later Rumsfeld ordered Garner to get rid of O’Sullivan and Warrick in preference for more Defense Department officials. When Garner pushed back, Rumsfeld claimed that the order had come from a higher level. Subsequently, Garner determined that Vice President Cheney had vetoed their assignment because he did not think that O’Sullivan and Warrick were sufficiently devoted to the Administration’s policy.

Second, Garner clashed on policy with the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith. Feith was 49, a lawyer by education, a lobbyist by vocation, and a neoconservative policy wonk. He was very close to Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz but was neither respected nor trusted by the Army General Staff. (2)

On 11 March, Garner gave a background briefing to the press on his planning for Iraq. When asked about rumors that the Defense Department wanted to make Ahmed Chalabi Iraq’s new president, Garner was bluntly dismissive. After the briefing in a private meeting, Feith shouted at Garner for being so disrespectful of Chalabi. By his own admission, Garner shouted back, “Doug, you’ve got two choices. You can shut the fuck up or you can fire me.” (3)

For the next six weeks Feith worked behind the scenes to raise doubts about whether Jay Garner ‘was sufficiently devoted to the Administration’s policy.’ On 21 April, twelve days after the statue of Saddam was toppled, Garner arrived in Iraq. On the night of 24 April, Garner was working in the looted mess of one of Saddam’s main palaces when Defense Secretary Rumsfeld called and politely fired him.

Paul Bremer and the Origins of the Sunni Insurgency

Following the brutal dictatorship of Saddam, an Iraqi insurgency was not inevitable … strategic mistakes born of American hubris made it so. An insurgency requires three things – weapons, money, and fighters willing to risk death. General Franks’ mistake in not assigning sufficient forces to secure Qa’qaa and other Iraqi weapons depots resulted in plenty of explosives being available to make roadside bombs. The money and fighters resulted from incredible mistakes made by Garner’s replacement as US governor of Iraq, Paul Bremer.

Bremer was 62, a Yale undergrad, Harvard MBA, and a high-flyer at the State Department including a stint as Secretary Henry Kissinger’s Special Assistant. At 49, he retired early from State to become Managing Director of Kissinger’s international consulting firm and subsequently became CEO of Marsh Crisis Consulting. Wolfowitz and Feith deemed him more politically reliable than Garner but Bremer had no hands-on experience in Iraq. His title was Presidential Envoy but his appointment letter explicitly declared him subject to the “authority, direction and control” of the Iraq Czar, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld.

On 12 May 2003, Bremer arrived in Baghdad and moved quickly. On 16 May, over the objections of his entire staff including the CIA Chief of Station, Bremer issued Coalition Provisional Authority Order #1 which purged 70,000 members of Saddam’s Bath Party from working in the Iraqi government. In one fell swoop Order #1 assured that the richest, most powerful people in Saddam’s Iraq would put their money to work against the Americans. On 23 May, Bremer issued Order #2 which abolished both the Iraqi military and their police forces, putting 700,000 weapon-trained Iraqi’s abruptly out of work, angry, and willing to fight.

Deadly attacks on US military forces started immediately. During June and July, these attacks seemed uncoordinated and were dismissed by Secretary Rumsfeld as the last gasp of “Saddam dead-enders.” During August-October, the attacks were clearly coordinated and focused on US allies and international organizations with the intent of driving a wedge between them and the US. In November, the insurgency shifted focus back to the US military and launched the Ramadan Offensive. Seventy US soldiers died that month from hostile action, more than during the “major combat operations” in either March or April. (4)

Chalabi had convinced Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Feith that US troops would be welcomed as liberators. They believed that the military operation to oust Saddam would be smooth after which our troops could quickly come home. When that proved not to be the case, Paul Bremer took the blame. At one Principals Meeting at the White House, the President’s National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice reminded Rumsfeld that Bremer worked for him. Rumsfeld shot back that “No he doesn’t,” asserting that Bremer was a Presidential Envoy.

Out policing the streets In Iraq, our uniformed military simply wanted an exit strategy. They argued that the key to quelling the insurgency was returning authority for governing Iraq to the Iraqis. Bremer, the all-powerful governor, did not like this idea. The White House though wanted to reduce the violence in Iraq before the 2004 Presidential elections in the US. So, on 12 November 2003, the President decided to return authority for governing Iraq to the Iraqis effective 30 June 2004.

One Bit of Good News followed by Two Bits of Really Bad News

On 13 December 2003, Bremer announced in English on Iraqi TV, “Ladies and gentlemen, we got him.” After nine months of searching, an intelligence tip led to the capture of Saddam Hussein near his hometown of Tikrit. For a period following the capture, attacks on US troops dropped dramatically. As 2004 began, everyone in the Bush Administration was optimistic that, absent Saddam’s leadership, the insurgency was finally on its last legs.

In January 2004, however, the primary justification for our invasion – Iraq’s alleged work on nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons of mass destruction – fell apart. The CIA’s Iraq Survey Group led by David Kay had been in Iraq since May looking for the WMD but had not found any. Kay was ready to wrap up his work in the Fall of 2003 but CIA Director George Tenet convinced him to keep looking. Finally, on 23 January, Kay resigned. In public testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on 28 January, Kay criticized the pre-war WMD intelligence and said, “it turns out we were all wrong.”

Understandably, the resulting political controversy was intense. As a face-saving measure, President Bush announced on 6 February the creation of the Silberman-Robb Commission to examine this intelligence failure and report back in March 2005, after the US Presidential elections. Under a cloud, Tenet resigned as CIA Director on 11 July 2004.

On top of the WMD controversy, the dignity of the US military and of the CIA was compromised by their abuse, torture, and killing of Iraqi detainees at the Abu Ghraib Prison west of Baghdad. Iraqi reports of abuse there began surfacing as early as June 2003. Although dismissed by US authorities, at least some of the reports turned out to be true, including the death of one suspected terrorist while in CIA custody. The scandal came to US public attention on 28 April 2004 when CBS News published photos of the suspected terrorist’s body and other squalid conditions inside the prison.

Secretary Rumsfeld offered to resign in responsibility for Abu Ghraib but his offer was rejected by President Bush. Nobody at CIA was prosecuted for the death due to Bush-era legal exemptions covering the Agency’s counter-terrorist operations. Only enlisted military personnel were criminally convicted for the abuse.

2004: Zarqawi Emerges

Following the arrest of Saddam Hussein, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi emerged as a key leader of the Sunni insurgency. Not an Iraqi, Zarqawi was a Jordanian national of Palestinian descent. Born in 1966, impoverished, and poorly educated, he survived as a street thug. During 1992-1999, Zarqawi served time in a Jordanian prison where he was easy prey for Sunni radicals who taught hatred of infidel Americans who supported Israel as well as hatred of apostate Shia Muslims. After release, he participated in the failed Al Qaeda plot to bomb the Radison Hotel in Amman at the end of the millennium. To avoid arrest he fled to Afghanistan where post-9/11 he was wounded fighting the Americans. In early 2003, he was in Iraq organizing a clandestine network to resist the forthcoming US invasion. In early 2004, he re-named his network Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), in part, to provoke the Americans. (5)

Zarqawi hid his headquarters amidst the densely populated city of Fallujah, the hotbed of the Sunni insurgency. He was immediately blamed for the infamous 31 March killing of four American security contractors and the desecration of their bodies on the Fallujah Iron Bridge. In response, the commander on the ground, Marine Major General (and future Defense Secretary) Jim Mattis proposed a slow but well-thought-out operation that would punish the killers without endangering innocent civilians. The White House, however, duly provoked and seeing an opportunity to divert public attention from the WMD fiasco, overruled Mattis and ordered a full attack on Fallujah within 72 hours. (6)

The precipitous attack backfired politically as General Mattis had anticipated, handing Zarqawi and the other insurgents a tactical victory. The attack began as ordered on 3 April. Decent Sunnis were appalled by the innocent civilian casualties and destruction. Moderate Sunni leaders who were helping Bremer put together an Iraqi government threatened to walk away. Likewise, United Nations Special Representative Lakhdar Brahimi threatened to pull out the UN Mission. Fearing collapse of the political transition, the White House backed down and on 9 April ordered Mattis to cease offensive operations. Thirty-seven of his Marines had died.

Invigorated by this success, Zarqawi tried to provoke the Americans again. In April, AQI operatives kidnapped a young American working in Iraq named Nick Berg. In early May, they dressed Berg in the same orange jump suit worn by prisoners in US custody at Abu Ghraib and then took a video as Zarqawi himself beheaded Berg with a knife. They dumped Berg’s body in Baghdad on 8 May and posted on the internet a video of the decapitation on 11 May.

By July, Bremer had departed, and the US had a skilled Ambassador in place – John Negroponte – who worked with the permission and support of our new, handpicked, Iraqi Prime Minister – Ayad Allawi – a Shia Muslim with reputedly a history of cooperation with the CIA. They did not react precipitously to the Berg beheading; instead, they methodically initiated a plan to kill Zarqawi. First, they raised the bounty for Zarqawi from $10 million to $25 million, the same that was being offered for Osama bin Laden. Then, they began to carefully plan a second attack on Zarqawi’s stronghold of Fallujah.

The most important lesson from the First Battle of Fallujah was that success in the Second Battle depended on a deliberate shaping of the political environment. In the months prior to this Second Battle, some 90% of Fallujah’s population of 300,000 was evacuated temporarily, leaving the 3,000 hardened insurgents more exposed. The US also guaranteed Prime Minister Allawi that humanitarian relief and reconstruction support would be provided to help citizens of the city recover once the battle was over. Finally – a White House priority – initiation of the attack was put off until 7 November, five days after President Bush won re-election.

West Point has produced an excellent summary of the Second Battle which is well worth reading for those interested in the essential tactics. In short, the Second Battle was a huge loss for the Iraqi insurgents including Zarqawi’s AQI. They never again dared to confront US forces in regular combat. But Zarqawi himself escaped, managing to slip out of the city around 8 November. (7)

State of Denial

Bob Woodward of The Washington Post wrote three books about George W. Bush as President. The first two – Bush at War and Plan of Attack – are admiring in tone. The third book is deeply disappointed in tone. Indeed, the title of this third book – State of Denial – reflects the remarkable wishful thinking about Iraq that Woodward could feel in his interviews with the President. Among the many anecdotes Woodward offers, two events stand out.

First, on 14 December 2004, Bush awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to George Tenet, Tommy Franks, and Paul Bremer in a joint ceremony. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is our nation’s highest civilian honor. Perhaps these men – particularly Tenet and Franks – deserved this honor for other reasons. The fact that the medals were awarded in a joint ceremony, however, made it plain to see that they were being honored for their role in Iraq. So, it is fair to ask: did the man who mistakenly provided the WMD justification for the invasion, the man who mistakenly invaded with an insufficient force, and the man who inadvertently prompted the Iraq insurgency through his General Orders #1 and #2 really merit our nation’s highest civilian honor?

Second, it is commonplace for a President to replace senior cabinet officers at the beginning of a second term, particularly the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense. Those jobs are excruciatingly hard, and four years is about the most one can expect of any human being. Thus, it was of no surprise when Colin Powell was asked to step down as Secretary of State. The huge surprise was that Donald Rumsfeld was asked to remain as Secretary of Defense. With NSD 24, the President had put Rumsfeld in charge of Iraq and – in my opinion – Rumsfeld failed miserably. As with Powell, the President could have graciously asked Rumsfeld to step down, no harm done. That Bush asked Rumsfeld to stay on is deeply revealing of the President’s state of denial about Iraq.

2005: The Insurgency Persists

The White House hoped that the Second Battle of Fallujah had finally broken the back of the insurgency and paved the way for successful Iraqi elections in January 2005. The insurgency persisted, however, with the US military suffering monthly deaths due to hostile action 7% higher during 2005 than they had been during the “major combat operations” period in 2003. Moreover, the number of US troops maimed monthly during 2005 was nearly double that of the “major combat operations” period because the insurgents had perfected their use of roadside bombs. (4)

Politically, we rejoiced when the January 2005 elections proceeded smoothly. We were unpleasantly surprised, however, when the Iranian backed Islamic Dawa Party of Iraq prevailed in those elections and named an ally of Iran as the new Prime Minister, Ibrahim al-Jaafari. For the White House, this created the awkward impression that American troops were being killed and wounded for the benefit of Iranian strategic interests.

Fearing betrayal in exchange for the $25 million bounty, Zarqawi hid out in Jordan after he escaped from Fallujah. On 9 November, he reminded us of his presence by sending suicide bombers to blow themselves up inside three American brand hotels in Amman – the Days Inn, the Grand Hyatt, and the same Radisson he had tried to bomb late in 1999. Sixty people were killed, including 4 Americans. The suicide bombers were all Iraqi and Zarqawi’s AQI immediately claimed responsibility.

2006: The Sunni-Shia Civil War

Zarqawi snuck back into Iraq in late 2005-early 2006 with a revised plan of attack. After Fallujah-2 he would not go face to face with US troops. Instead, he ignited a civil war in hopes of uniting Iraq’s Sunni Muslims to fight the Shia Muslims who were now running the government, leaving US troops caught in the middle. The spark that set off the civil war was the 22 February bombing of the Al-Askari Shrine in Samarra, one of the holiest sites for Shia. Shia’s retaliated by murdering over 100 Sunni’s in the following 24 hours. The Sunni’s reciprocated in kind.

The US intensified the hunt for Zarqawi and finally got one of his aides to betray him in exchange for the $25 million. He was killed by a targeted US airstrike on 7 June. Almost immediately, however, Zarqawi was replaced by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi. In October, Baghdadi changed the name of Al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Islamic State of Iraq. The civil war further intensified. At the height of the sectarian violence during October 2006-January 2007, 3500 Iraqi civilians were being murdered each month.

By the US mid-term elections on 7 November 2006, America’s war in Iraq had been dragging on for three and a half years with no end in sight. The American voter showed displeasure, handing over control of both the Senate and the House to the Democrats. Finally shaken from his state of denial, the President accepted the resignation of Defense Secretary Rumsfeld on 8 November.

2007: An Exit Strategy

Bush named his father’s CIA Director and Brent Scowcroft protégé, Robert Gates, to be the next Defense Secretary. Gates’ assignment was to get the US out of Iraq with honor. To this end, in January Gates appointed General (and future CIA Director) David Petraeus as commander of US and allied troops in Iraq.

From his early days, Petraeus was skilled at developing relationships that were useful in promoting his military career. As a senior at West Point in 1974, he dated and subsequently married the daughter of the West Point Superintendent, General William Knowlton. Petraeus was aide to General John Galvin first in 1981 when the latter commanded the 24th Infantry Division and then later when Galvin served as the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. In 1998, Petraeus was executive assistant to General Henry Shelton, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Petraeus had a PhD from Princeton but was 50 years old the first time he saw combat during the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 as the Two Star General in command of the 101st Airborne Division.

Defense Secretary Gates selected Petraeus because he had been the only US division commander in Iraq who saw the need to win the hearts and minds of the Iraqi’s living in his zone of control. That was exactly the type of military leader that Gates needed to get the US out of the Iraq quagmire with honor.

Without question, Petraeus succeeded brilliantly. He won the hearts and minds of Sunni moderates who wanted to get on with their lives and killed Sunni radicals who offered nothing but a terrorist agenda. Next, he won over Shia moderates who were loyal to Iraq and killed Shia radicals who served Iranian interests. He became known amongst Iraqi’s as “King David”.

During 2008 violence in Iraq fell dramatically. US military casualties there during President Bush’s last year in office plummeted over 70 percent as well. This allowed the President on 14 December 2008 to sign an agreement with Iraqi Prime Minister Nour al-Maliki for the complete withdrawal of US troops by the end of 2011, an agreement fulfilled by President-Elect Obama.

During the signing ceremony in Baghdad, the President noted that such an agreement would have been “unimaginable” just two years before. Shortly after this comment, a frustrated Iraqi Shia journalist threw his shoes at Bush in protest. Not wanting to disrupt the solemn occasion, the President reacted with humor and grace, laughing that the shoes were size ten.

Performance Assessment

An assessment of the CIA’s performance during the Second Iraq War is indelibly colored by our mistaken WMD allegations used to justify the war in the first place. This is especially true of leadership performance which I continue to rate negatively as a (-). CIA operators did well in accurately reporting what was happening on the ground in Iraq during the war but sullied the dignity of the Agency with their abusive treatment of prisoners. Overall, I rate their performance a (0). CIA analysts had learned from the ill-fated National Intelligence Estimate on WMD. In January 2003, the analysts wrote another NIE entitled “Principal Challenges in Post-Saddam Iraq” which absolutely nailed the problems the US would face, including the possibility of a violent insurgency. For that, I rate the analysts positively with a (+). (8)

First and foremost, however, the Second Iraq War was a tragic failure of policy and political leadership. The insurgency was caused by three fateful decisions – the insufficient size of the invasion force, the excessive purging of the Bath Party, and the abolition of Iraq’s military and police forces – that were driven by the domineering civilian leadership of the Defense Department – Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Feith – with scant regard for the cautionary advice offered by the uniformed military and the CIA. President Bush, as gracious a man as he was, stubbornly backed Defense Secretary Rumsfeld for 6 years until the situation had become, in his own words, “unimaginable”. Only when the American voter rebelled, did Bush change course.

The President deserves considerable credit for finally accepting reality and changing course but to this day many Iraqis, both Shia and Sunni, have undying respect for the shoe thrower.

Footnotes

(1) Michael Gordon & General Bernard Trainor, Cobra II, page 349.

(2) General Franks called Feith “the dumbest fucking guy on the planet”; Thomas Ricks, Fiasco, page 78.

(3) Thomas Ricks, Fiasco, page 105.

(4) US Defense Department, Operation Iraqi Freedom Casualty Summary by Month and Service

(5) Craig Whitlock, Al-Zarqawi’s Biography, Washington Post 8 June 2006.

(6) Months later it was determined that Zarqawi was probably not responsible for the ambush.

(7) West Point Modern War Institute, Urban War Institute Case Study #7 – Fallujah 2

(8) For the Key Judgements of this NIE see Michael Gordon & General Bernard Trainor, Cobra II, pp 570-571.